Kidney Transplantation

What is a kidney transplant?

A kidney transplant is a surgical procedure. It's done to implant a healthy kidney from another person. The kidney may come from a deceased donor or from a living donor.

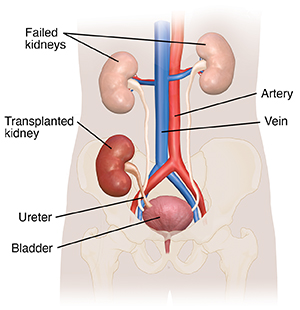

A person getting a transplant often receives only one kidney. But in rare cases, they may receive two kidneys. Often, the diseased kidneys are left in place during the transplant. The transplanted kidney is put in the lower abdomen on the front side of the body.

Why is a kidney transplant recommended?

A kidney transplant is advised for people who have end-stage kidney disease and will not be able to live without dialysis or a transplant. In the U.S., the most common causes of end-stage kidney disease are diabetes and high blood pressure. There are also many other causes of this disease. Always talk with your healthcare provider for a diagnosis.

How many people in the U.S. need kidney transplants?

Visit United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) to find statistics of patients awaiting a kidney transplant. You can also see the number of patients who had a transplant this year.

Where do transplanted organs come from?

Most kidneys that are transplanted come from deceased organ donors. Organ donors are adults who have become critically ill and are pronounced dead because their brain or heart has stopped working permanently. Kidneys are taken after these adults are pronounced dead. The family of the dead person needs to agree to donate the person's organs. Donors can come from any part of the U.S. This type of transplant is called a deceased donor transplant.

A person having a transplant often gets only one kidney. But in rare cases, they may receive two. Medical experts are working to see if they can split one kidney for two recipients.

Family members or individuals who are unrelated, but make a good match, may also be able to donate one of their kidneys. This type of transplant is called a living transplant (living donor). People who donate a kidney can live healthy lives with one kidney. A child older than 2 years can generally get an adult kidney. There is often enough space in the belly for the new kidney to fit.

How are transplanted organs allocated?

UNOS is responsible for transplant organ distribution in the U.S. UNOS oversees the allocation of many different types of transplants. These include kidney, liver, pancreas, heart, lung, cornea, bone, and skin.

UNOS gets data from hospitals and medical centers throughout the country regarding adults and children who need organ transplants. The medical transplant team that currently follows you is in charge of sending your data to UNOS and updating it as your condition changes.

As of December 4, 2014, the newly revised kidney allocation system (KAS) has been in place. This new system was designed to improve transplant opportunities for all candidates. It gives better access to patients who often wait longer due to blood type or other reasons. If you were already on a waiting list before the new KAS was put into effect, you will not lose your place in line. Talk with your healthcare provider about the new KAS guidelines.

When a donor organ becomes available, a computer searches all the people on the waiting list and sets aside those who are not good matches for the kidney. A new list is made from the remaining candidates. The person at the top of the list is considered for the transplant. If they are not a good candidate, for whatever reason, the next person is considered, and so forth. Some reasons that people lower on the list might be considered before a person at the top include the size of the donor organ and the geographic distance between the donor and the recipient.

How am I placed on the waiting list for a new kidney?

An extensive evaluation must be done before you can be placed on the transplant list. Testing includes:

Blood tests are done to gather information that will help determine how urgent it is that you are placed on the transplant list. They also make sure that you get a donor organ that is a good match. Some of the tests you may already be familiar with. You may have had them to evaluate the health of your kidney and other organs. These tests may include:

-

Blood chemistries. These may include serum creatinine, electrolytes (such as sodium and potassium), cholesterol, and liver function tests.

-

Clotting studies, such as prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT). These tests measure the time it takes for blood to clot.

Other blood tests will help improve the chances that the donor organ will not be rejected. They may include:

-

Your blood type. Each person has a specific blood type: type A+, A-, B+, B-, AB+, AB-, O+, or O-. When getting a transfusion, the blood received must be a compatible type with your own. Or an allergic reaction will happen. The same allergic reaction will happen if the blood contained within a donor organ enters your body during a transplant. Allergic reactions can be prevented by matching the blood types of you and the donor.

-

Human leukocyte antigens and panel reactive antibody (PRA). These tests help determine the likelihood of success of an organ transplant. They check for antibodies in your blood. Antibodies are made by the body's immune system in reaction to a foreign substance, such as a blood transfusion or a virus. Antibodies in the bloodstream will try to attack transplanted organs. So people who get a transplant will take medicines that decrease this immune response. The higher your PRA, the more likely that an organ will be rejected.

-

Viral studies. These tests see if you have viruses that may increase your chance of rejecting the donor organ, such as cytomegalovirus. Many other infectious diseases are also tested for, including HIV and hepatitis.

Diagnostic tests are done to understand your complete medical status. Many of these tests are decided on an individual basis:

-

Renal ultrasound. During this noninvasive test, a transducer is passed over the kidney. It makes sound waves that bounce off the kidney, sending a picture of the organ to a video screen. The test is used to determine the size and shape of the kidney. It can also find a mass, kidney stone, cyst, or other obstruction or abnormalities.

-

Kidney biopsy. For this procedure, tissue samples are removed (with a needle or during surgery) from the kidney. They are examined under a microscope. This test is done to determine if cancer or other abnormal cells are present.

-

Intravenous pyelogram. This is a series of X-rays of the kidney, ureters, and bladder. A contrast dye is injected into a vein to find tumors, abnormalities, kidney stones, or any obstructions.

The transplant team will consider all information from interviews, your medical history, physical exam, and diagnostic tests in deciding whether you can be a candidate for a kidney transplant. After you have been accepted to have a kidney transplant, you will be placed on the UNOS list.

If you are getting a kidney donated by a living donor, the donor will have a similar evaluation.

The transplant team

During the evaluation process, you will be interviewed by many members of the transplant team, such as:

-

Transplant surgeons. Healthcare providers who specialize in organ transplants and who will be doing the surgery.

-

Nephrologist. A healthcare provider who specializes in disorders of the kidneys. Nephrologists will help manage your condition before and after the surgery.

-

Transplant nurse coordinator. A nurse who organizes all aspects of care provided to you before and after the transplant. The nurse coordinator will provide education and coordinate the diagnostic testing and follow-up care.

-

Social workers. Experts who will help your family deal with many issues that may come up, such as lodging and transportation, finances, and legal issues.

-

Dietitians. Experts who will help you meet your nutritional needs before and after the transplant.

-

Physical therapists. Healthcare providers who will help you become strong and independent with movement and endurance after the transplant.

-

Pastoral care. Chaplains who provide spiritual care and support.

-

Other team members. Several other team members will evaluate you before the transplant and will make recommendations to the team. These include:

How long will it take to get a new kidney?

There is no definite answer to this question. If you have a compatible and healthy living donor, you may be able to get a transplant within a few weeks or months. If no living-related donor is available, it may take months or years on the waiting list before a suitable donor organ is available. During this time, you will receive close follow-up with your healthcare providers and the transplant team. Support groups are also available to help you during this waiting time.

How am I notified when a kidney is available?

Each transplant team has its own specific guidelines regarding waiting on the transplant list and being notified when a donor organ is available. In most cases, you will be notified by phone or pager that an organ is available. You will be told to come to the hospital right away so that you can be prepared for the transplant.

What is rejection?

Rejection is a normal reaction of the body to foreign tissue. When a new kidney is placed in a person's body, the body sees the transplanted organ as a threat and tries to attack it. The immune system makes antibodies to try to kill the new organ. It does not realize that the transplanted kidney is beneficial. To allow the organ to successfully live in a new body, medicines must be given to trick the immune system into accepting the transplant and not thinking it is a foreign object.

What is done to prevent rejection?

Medicines must be given for the rest of your life to fight rejection. Each person is individual, and each transplant team has preferences for different medicines. The antirejection medicines most commonly used singly or in combination include:

-

Cyclosporine

-

Tacrolimus

-

Azathioprine

-

Mycophenolate mofetil

-

Prednisone

-

OKT3

-

Antithymocyte Ig

New antirejection medicines are continually being approved. Healthcare providers tailor medicine regimes to meet the needs of each individual.

Often several antirejection medicines are given initially. The doses of these medicines may change often as your response to them changes. Because antirejection medicines affect the immune system, people who receive a transplant will be at higher risk for infections or even certain types of cancer. A balance must be kept between preventing rejection and making you very prone to infection. Blood tests to measure the amount of medicine in the body are done periodically. They make sure you do not get too much or too little of the medicines. White blood cells are also an important indicator of how much medicine you need.

The risk of infection is especially great in the first few months. That's because higher doses of antirejection medicines are given during this time. You will most likely need to take medicines to prevent other infections from happening.

What are the signs of rejection?

These are some of the most common symptoms of rejection:

Your transplant team will instruct you on who to call right away if any of these symptoms happen.

Long-term outlook for a person after a kidney transplant

Living with a transplant is a lifelong process. You must take medicines to trick the immune system so it will not attack the transplanted organ. You must also take other medicines to prevent side effects of the antirejection medicines, such as infection. You will have frequent visits to and contact with your transplant team. It's important that you know the signs of organ rejection and watch for them on every day.

Every person is different and every transplant is different. The new antirejection medicines that are being approved are promising. Results improve continually as healthcare providers and scientists learn more about how the body deals with transplanted organs and search for ways to improve the success of transplants.